The evolution of spatial computing interfaces has been one of the most fascinating technological journeys of the past few decades. From rudimentary command-line inputs to immersive augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) environments, the way humans interact with machines has undergone a radical transformation. This shift hasn’t just changed how we perform tasks—it has redefined the very nature of human-computer interaction.

Early Days: The Birth of Graphical Interfaces

In the beginning, computing was a text-heavy affair. Users typed commands into terminals, and machines responded with lines of code. The introduction of graphical user interfaces (GUIs) in the 1980s marked a turning point. Suddenly, icons, windows, and pointers became the norm, making computers accessible to a broader audience. The mouse and keyboard became the dominant input devices, setting the stage for decades of interaction design.

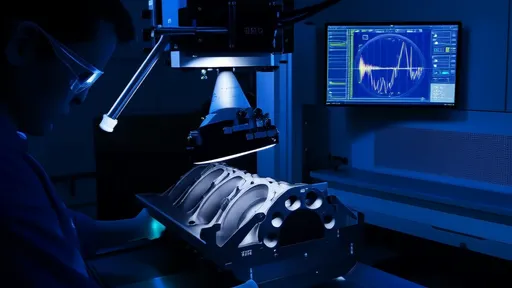

The Rise of Touch and Gesture Controls

Touchscreens revolutionized spatial interaction by allowing direct manipulation of digital objects. Smartphones and tablets made multi-touch gestures—pinching, swiping, tapping—second nature to billions of users. Meanwhile, motion-sensing technologies like Microsoft’s Kinect explored gesture-based controls, proving that our bodies could serve as input devices. These advancements hinted at a future where physical and digital spaces would blend seamlessly.

Spatial Computing and the Era of Immersion

Today, spatial computing devices like AR glasses and VR headsets are pushing boundaries further. Instead of interacting with flat screens, users engage with three-dimensional environments. Hand tracking, eye tracking, and voice commands enable more intuitive control. Devices like the Meta Quest and Apple Vision Pro demonstrate how spatial interfaces can merge the real and virtual worlds, creating experiences that feel natural and immersive.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite rapid progress, spatial computing still faces hurdles. Latency, field of view limitations, and user fatigue remain significant concerns. Moreover, designing interfaces for three-dimensional spaces requires rethinking traditional UX principles. As AI and machine learning improve, adaptive interfaces that learn from user behavior could become the next frontier. The goal is clear: to create interactions so seamless that the technology itself fades into the background.

The journey from text-based commands to spatial computing has been long, but it’s far from over. Each leap forward brings new possibilities—and new questions—about how humans and machines will coexist in an increasingly digital world.

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025

By /Jul 11, 2025