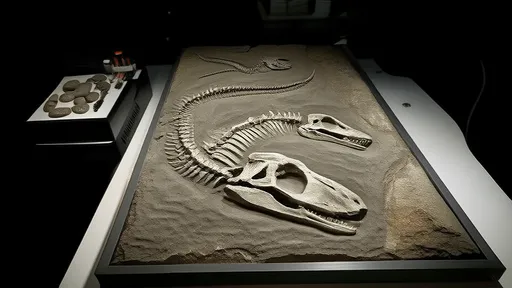

The art of transferring fossil impressions and rock layer textures onto paper or other surfaces has long fascinated paleontologists and artists alike. Known as fossil rubbing or rock texture transfer, this technique bridges the gap between scientific documentation and aesthetic expression. Unlike traditional photography or 3D scanning, it captures minute details through direct physical contact, preserving the tactile essence of ancient surfaces.

Historical Roots and Modern Adaptations

Centuries ago, scholars in China pioneered early forms of fossil rubbing using rice paper and ink to record inscriptions. This practice evolved into a method for preserving delicate fossil imprints without damaging specimens. Today’s practitioners employ advanced materials like Japanese kozo paper and water-soluble inks, which conform to uneven surfaces more effectively than traditional mediums. Field researchers often carry portable kits containing synthetic tracing films—a nod to the past adapted for contemporary science.

The process begins with meticulous surface preparation. Loose particles are stabilized using consolidants like Paraloid B-72, a reversible acrylic resin favored by conservators. This step prevents flaking during transfer while maintaining the specimen’s integrity. Unlike digital replication methods, the manual pressure applied during rubbing reveals subtle features—micro-fractures in dinosaur bone or ripple marks from prehistoric tides—that might escape electronic sensors.

The Dance of Pressure and Perception

Mastering variable pressure constitutes the technique’s soul. Too forceful, and delicate structures crumble; too gentle, and details vanish. Veteran practitioners develop a tactile sensitivity comparable to a surgeon’s touch. The Smithsonian’s 2018 study demonstrated how controlled pressure gradients can distinguish overlapping fossil layers invisible under CT scanning. This hands-on approach frequently uncovers new data—a theropod’s feather quill knobs or fish gill filaments—during the transfer process itself.

Innovative hybrid methods now merge analog and digital workflows. Paleoartist Rachel Huling pioneered a technique where rubbed textures are scanned and computationally enhanced to separate superimposed elements. Her work on Wyoming’s Green River Formation revealed previously indistinguishable mayfly wing veins through layered digital subtraction of rock matrix patterns.

Beyond Documentation: The Artistic Frontier

Contemporary artists have appropriated these methods for creative ends. Boston-based collective Stratagraph produces large-scale installations by transferring entire cliff face sections onto biodegradable fabrics. Their 2022 "Deep Time Tapestry" incorporated actual Jurassic-period mudcrack patterns into woven designs, challenging distinctions between scientific record and artwork. Such projects raise provocative questions about humanity’s relationship with geological time—the very act of transfer becoming a meditation on impermanence.

Conservation debates simmer around the ethics of repeated rock surface contact. While the technique is non-invasive compared to extraction, some argue that popular fossil sites risk degradation from amateur rubbing attempts. The Paleontological Society now offers certification courses in proper field transfer protocols, emphasizing reversible materials and minimal-interaction principles derived from art restoration ethics.

Technological Cross-Pollination

Unexpected applications emerge in unexpected fields. Geotechnical engineers now use modified rock rubbing techniques to analyze dam foundation stability, capturing crack propagation patterns more accurately than laser profilometry in certain sedimentary formations. Meanwhile, the fashion industry experiments with fossil texture transfers for avant-garde textile designs—one Parisian atelier recently debuted a "Cambrian Collection" featuring brachiopod shell patterns heat-transferred onto silk.

The future may lie in smart materials. MIT’s Tangible Media Lab is developing pressure-sensitive films that change color according to subsurface density variations during rubbing. Such innovations could transform field paleontology, allowing real-time visualization of fossil bone density differences invisible to the naked eye. Yet as technology advances, practitioners maintain that the human element—the trained hand interpreting geological narratives through fingertips—remains irreplaceable.

From its scholarly origins to multidisciplinary applications, fossil texture transfer endures as both practical tool and poetic practice. It reminds us that some dialogues with the ancient Earth are best conducted not through screens or machines, but through the intimate whisper of paper against stone.

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025

By /Jul 16, 2025